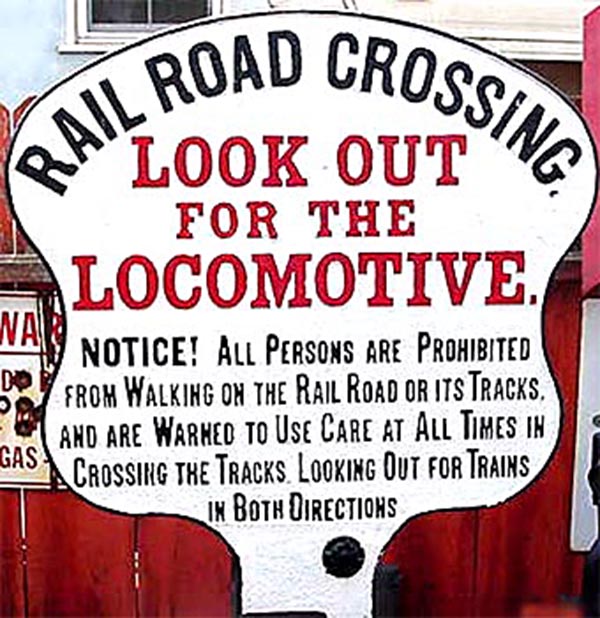

As America became laced with railroads in the latter half of the 19th century, it soon became apparent that safety warning signs and signals should be set up to protect people who wanted to cross the tracks.

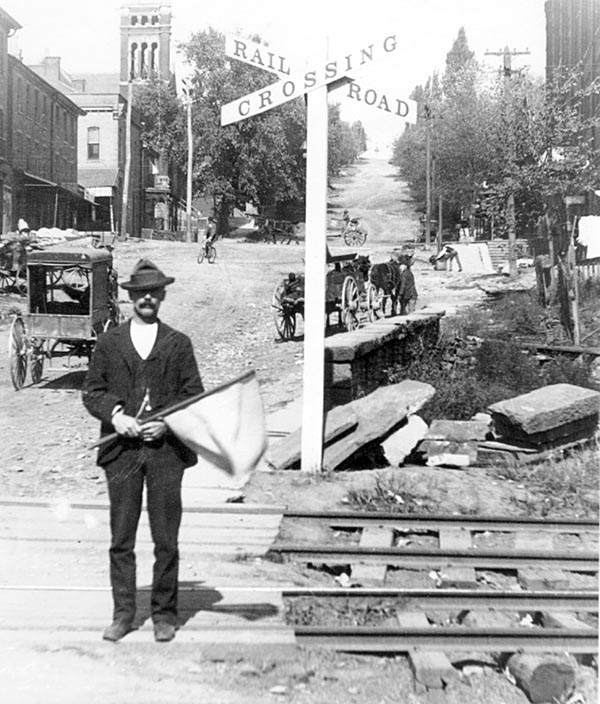

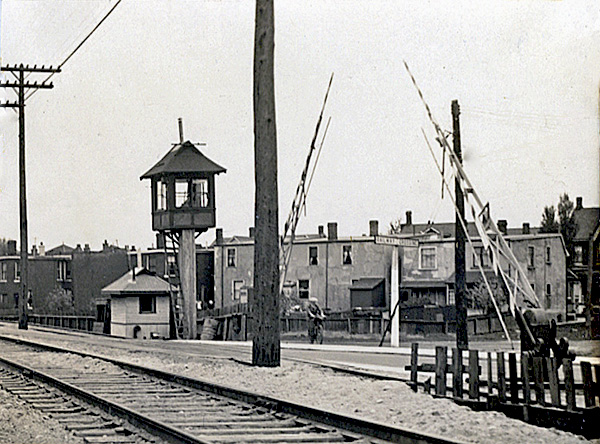

Initially, a variety of signs were posted at crossings, and in time, watchmen were stationed at the busier crossings to warn of approaching trains.

The first U.S. patent given for a railroad crossing gate dates back to August 27, 1867, and was awarded to J. Nason and J. Wilson of Boston Massachusetts.

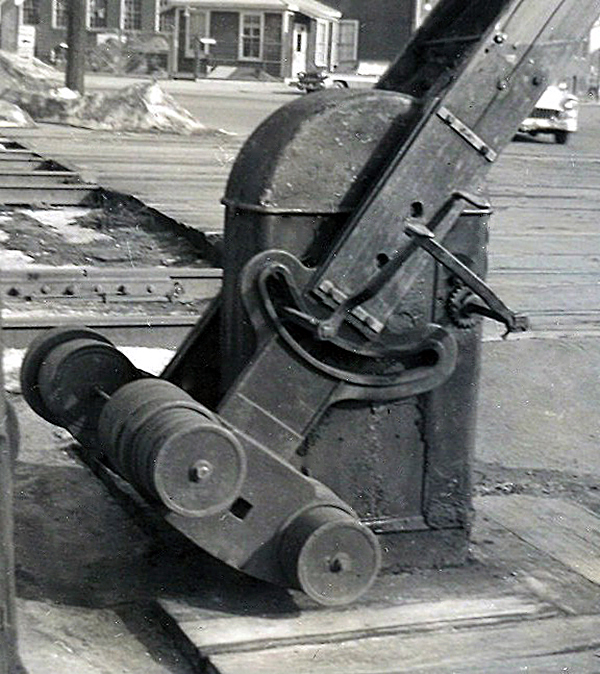

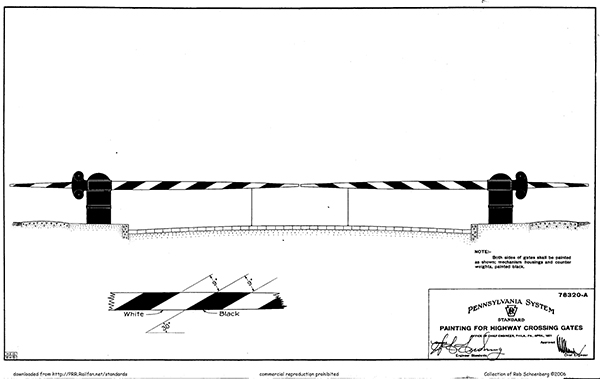

At that time, crossing gates were hand-operated by means of a crank mechanism. The gates were lowered and raised by means of cables or chains running through underground piping from the gatekeeper’s crank base to each individual gate at the crossing. Generally, each crossing had four separate gates. Due to the extreme length and great weight of the wooden gates, they had to be counterbalanced by very heavy cast-iron weights at their bases. Snow or rain could cause the wooden gates to become even heavier than they normally would be. Additional weight could be added to the massive counterweights as needed by the gatekeeper, who would place cast-iron disks, each weighing approximately 20 – 30 pounds apiece. As a train approached, the gatekeeper would crank the gates, and these would remain down until the train passed safely.

The classic wooden crossing gates displayed at the Whippany Railway Museum were manufactured by the Railway Safety Gate Company of Pawtucket, RI in the early 1900’s. They were originally in use at the West Side Avenue crossing on the former Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) line to Exchange Place in Jersey City, NJ. The tracks were also used by PRR subsidiary, Hudson & Manhattan RR (later to become Port Authority Trans – Hudson or PATH). When the crossing was permanently closed on April 30, 1967, the venerable gates, bases, counterweights and watchman’s crank base were acquired by the Morris County Central RR (a steam-powered excursion line operating out of Whippany, NJ in the 1960’s). The gates were first set up for display at Whippany in 1968. Since that time they have been restored several times over the years by Museum volunteers.

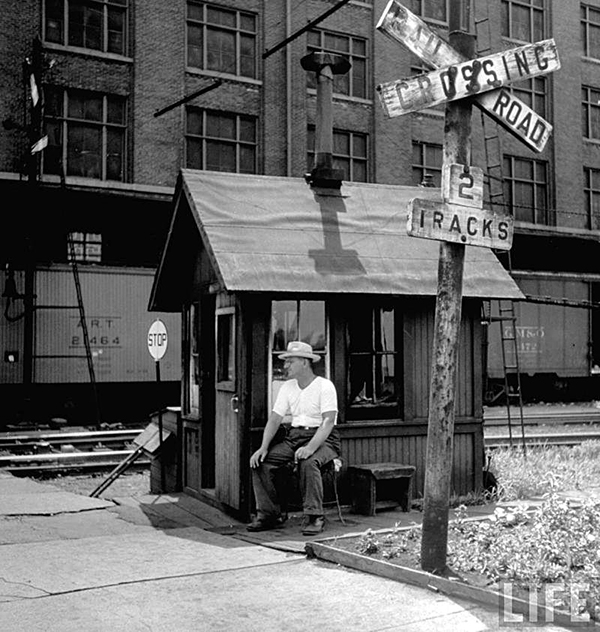

Gatekeepers usually had some kind of shelter for the times between trains, and some of these were elevated as either the second story of a structure, or were sometimes perched on a wood or steel structure reached by a ladder. At the Whippany Railway Museum, a replica Pennsylvania Railroad crossing shanty has been erected to give visitors an example of these unique, little buildings.

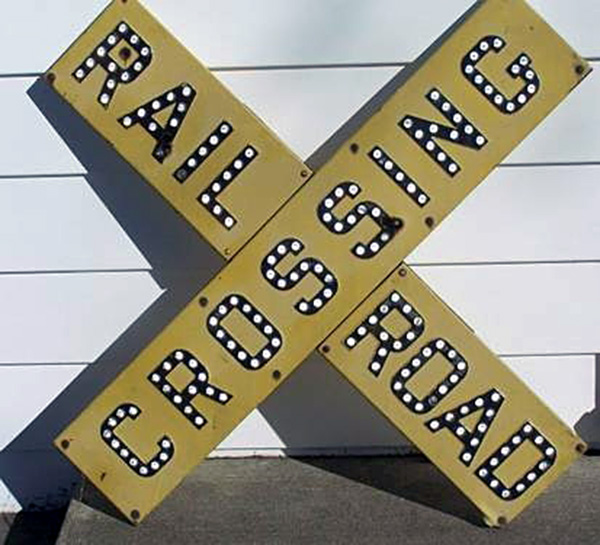

By the early 20th century, the use of “crossbuck” signs (the boards forming an “X”), were very common. The design formed the basic warning sign still in use today, but vastly improved with automatic warning advances. In the mid-1920s, sign makers began using road reflectors called Cataphote reflectors or “cats eyes” on crossbuck signs to make them more visible to drivers at night. These were used through the mid-1940s, when reflective buttons became common. Eventually, reflective sheeting gained popularity. Today, the material is still used to make street and railroad crossing signs.

Since it wasn’t practical to have employees stationed at all railroad crossings, a way was sought to automatically alert the public that a train was approaching.

The first automatic crossing signals were bells mounted atop poles. They were activated when a train entered a circuit where the rails were insulated to confine the electric current to a designated piece of track. The current flowed through the steel wheels and axles of the train, short-circuiting electricity to a relay which needed the power to hold the electrical connection apart that kept the bell off. When the electricity was diverted through the train…(which was a path of lower resistance)…instead of the relay connection, the contacts connected and the bell rang.

The electric bell idea was quickly expanded to include a swinging round sign with a red light hanging from an arm on the signal pole to simulate a flagman waving a red lantern. The “Automatic Flagman” signals were soon dubbed “Wig-Wags”. Only a very few Wig-Wags remain in use today in the United States, much beloved by rail enthusiasts for their nostalgic warning. One historic Wig-Wag signal from the early-1930’s (formerly in use on the Susquehanna Railroad just West of Butler, NJ) is currently being restored for operation at the Whippany Railway Museum.

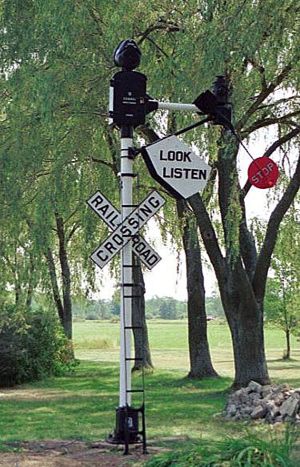

Eventually the Wig-Wags gave way to the alternating flashing red lights mounted as part of a cross-buck sign, and often with the crossing gates as well. The first flashing red light signal was installed in New Jersey in 1913.

At the Museum site, a fully-functional 1940’s-era Crossing Flasher from the Central Railroad of New Jersey warns visitors of approaching excursion trains. With it’s twin flashing red lights, cast-iron crossbucks and warning bell, the signal is a classic example of mid-20th Century grade crossing protection.

A prototype railroad crossing signal that was built in Grenada, Mississippi in the mid 1930’s at a railroad crossing that was considered especially dangerous. The design attempted to get motorists to stop with a combination of visually dramatic graphics, lights and sound. The words “STOP – DEATH – STOP” were illuminated with neon lights that would flash when a train approached. An arrow indicated the direction of the approaching train. The skull and cross bones was also neon-lit and flashed from red to blue. A more traditional pair of flashing lights was also included. If that was not enough, the signal also featured an ear-splitting air raid siren.

Today the basic designs come in a wide variety of configurations, depending on the complexity of the street crossing and the railroad company. Each one is custom designed to fit a specific need.

Originally, wooden crossing gates protected the entire width of the roadway. But in the later-half of the 20th Century, most crossing gates were re-designed to protect against motor traffic only in the oncoming lanes…covering only half the street, allowing an “escape” from the tracks for motorists who happened to be on the crossing when the signal was activated.

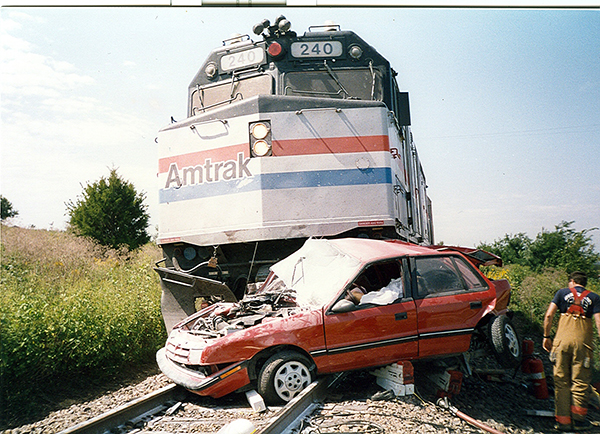

With a terrifying number of motorists increasingly ignoring the crossing gates and winding up being involved in a deadly accident, the use of “four quadrant gates” currently is being implemented around the country to prevent motorists from driving around lowered gates.

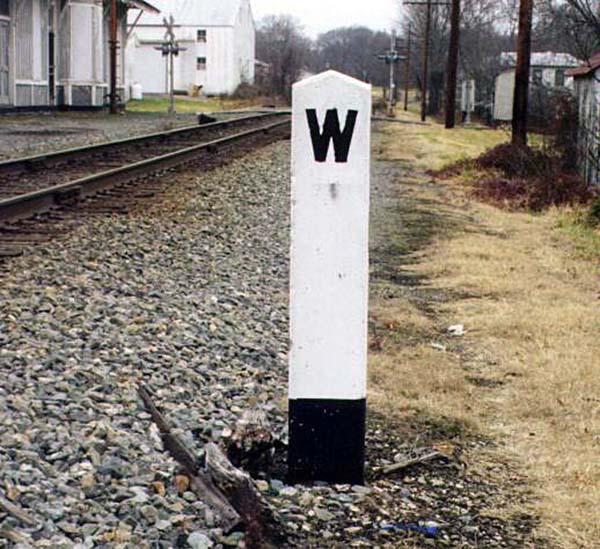

In addition to the signals and signs, operating rules require train crews to sound the locomotive horn or whistle a quarter of a mile in advance of each public crossing until they cross the roadway. Modern locomotives are equipped with a triangle of bright headlights, one mounted high and centered, and two on each lower side of the front of the engine. As soon as the horn begins to sound, the lower twin lights are illuminated and flash alternately.

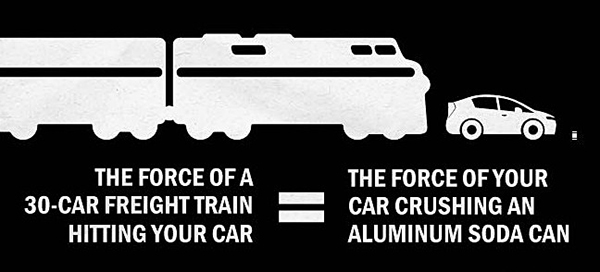

Since physics makes it impossible to stop a moving train in time to avoid striking a motorist or pedestrian on the track by the time the train crew realizes the danger, the public must always take extreme care when approaching railroad tracks. It takes more than half a mile to stop a heavy freight train, even when emergency braking is used.

Signals, signs, lights, whistles and horns are important safety aids, but ultimately it is the motorist’s responsibility to determine whether or not it is safe to cross the tracks.

Always remember to STOP, LOOK AND LISTEN !