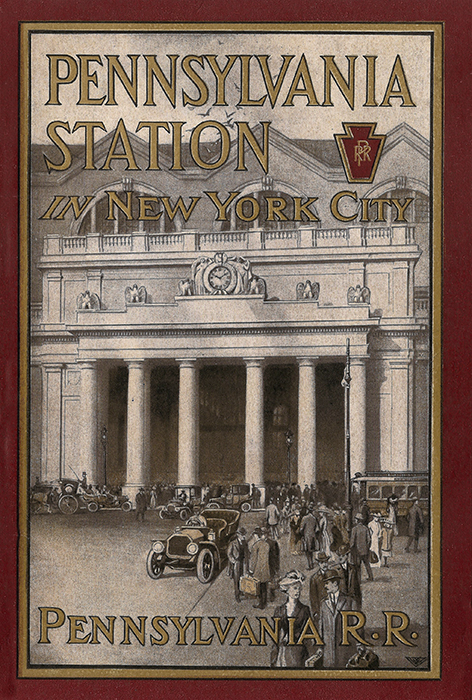

From Pennsylvania Station – New York

‘Old’ Penn Station

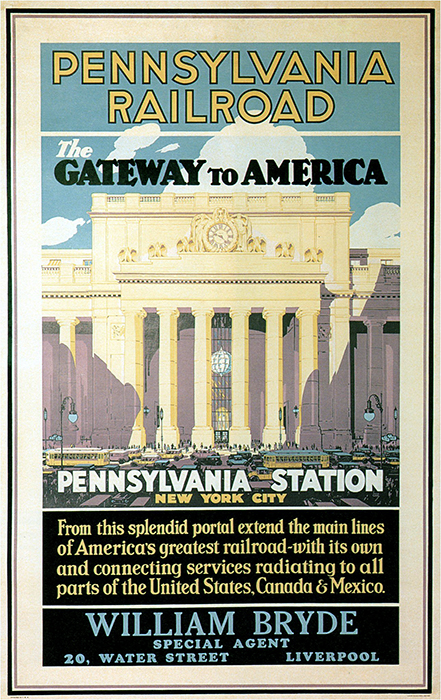

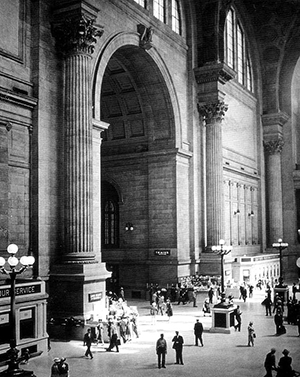

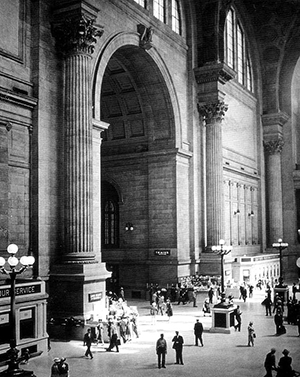

Opened to the public on November 27, 1910, New York City’s original Pennsylvania Station, designed by Beaux-Arts architects McKim, Mead and White, was a grand temple to rail travel bounded by Seventh and Eighth Avenues and 30th and 33rd Streets. The Seventh Avenue façade was dominated by a colonnade of granite pillars modeled after the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. The main waiting room, designed to echo the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, featured a giant barrel-vaulted ceiling as high and long as the nave of Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. The main departure concourse featured a dramatic glass train shed which brought ample sunlight down to the train platforms themselves. Richly detailed sculptures abounded, including 22 statues of giant eagles which once perched all along the cornice of the station.

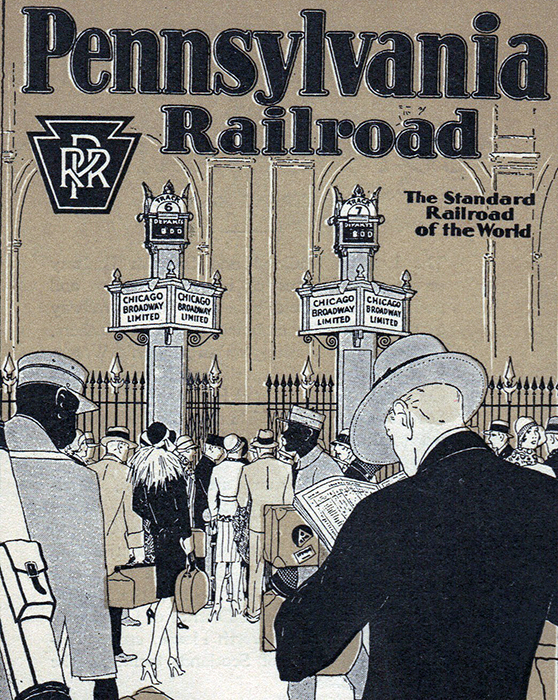

The Pennsylvania Railroad’s (PRR) enormous station gave the traveler, visitor, and commuter alike an experience of grandeur never before seen in the United States. Pennsylvania Station was a monument not only to “The Standard Railroad of The World” (the PRR), but was an architectural icon of New York City and one of the grandest public buildings of the 20th Century.

The station occupied four city blocks; yet one was never confused by its vastness. Patrons progressed easily from the European-like elegance of the arcade to the opulent magnificence of the main waiting room and then to the drama and movement of the concourse. Charles McKim’s brilliance was evident in his ability to break up the spaces so that each was a different experience and all were related.

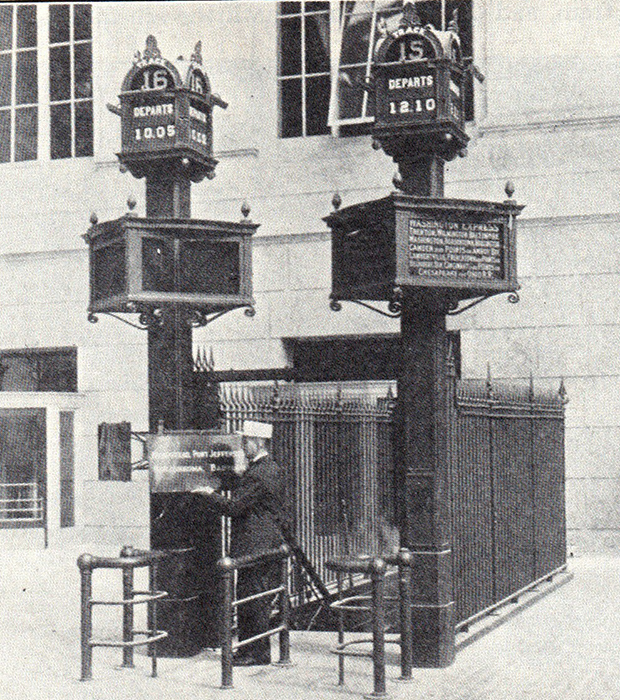

With acute attention to detail, even the Train Indicators, placed at the boarding gates, had been specially designed to conform to the ornate iron fencing that enclosed the platform area. Each Indicator stood sixteen feet high, and was of cast-iron, painted black. The aluminum sign cards, which displayed the name of the train as well as its stops, were painted bright red, the only touch of color in the room of black and gray. (During a 1950’s revamping of Penn Station, the Train Indicators were given a coat of steel-gray paint while retaining the red sign cards.)

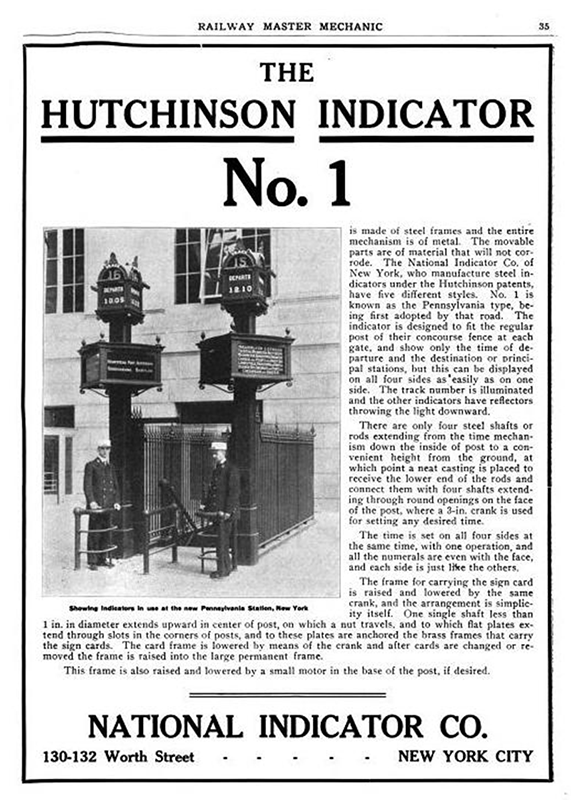

As the 1900’s ended its first decade, there were at the time about six general types of devices in use for the purpose of aiding an intending passenger to find his train after purchasing his ticket and checking his baggage. The most modern of these indicators in 1910 were the Hutchinson Indicators manufactured by the National Indicator Company (NIC) of New York. NIC had installed indicators at Grand Central Terminal and Pennsylvania Station in New York City, the Central RR of NJ Terminal in Jersey City, NJ, as well as Michigan Central Station in Detroit, the Great Northern Station in Minneapolis and Kansas City’s Union Station.

The Indicators at Penn Station were somewhat out of the ordinary, and as noted above, they formed a part of the fence along the concourse and fit in with the artistic theme of the facility. The Penn Station Indicators featured sign cards measuring 17 by 32 inches, and were carried on a light metal frame, inside of the larger frame. This inner frame was lowered by means of a small crank inserted in a hole near the base of the main post . The movable parts were operated by five, half-inch shafts, by means of miter gears and universal joints. The track number at the top was illuminated from within, but the rest of the lettering was lit by outside reflectors. The numerals used for showing the time were on steel ribbons, enameled on both sides. A single crank served to move both the name card and time ribbon.

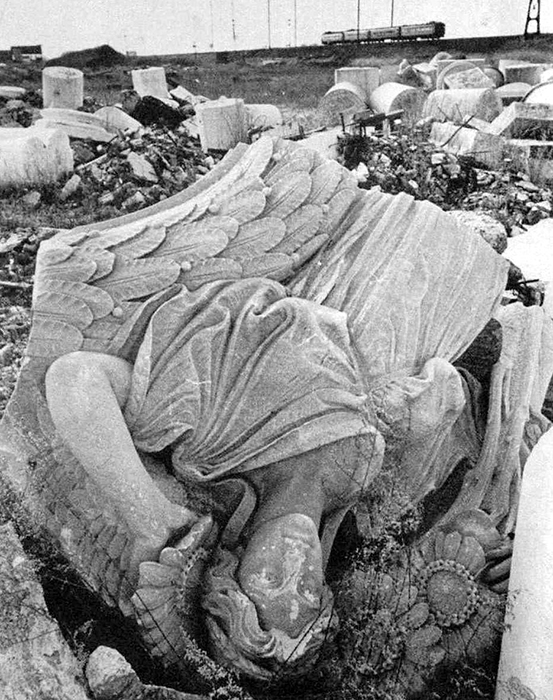

McKim, Mead and White had intended for their masterpiece to survive for 500 years; it barely lasted 53. In 1962 the PRR made the decision to demolish the station as rail travel gave way to the airlines. No one could have foreseen that the destruction of Pennsylvania Station would prove to be one of the key moments in the birth of the historic preservation movement.

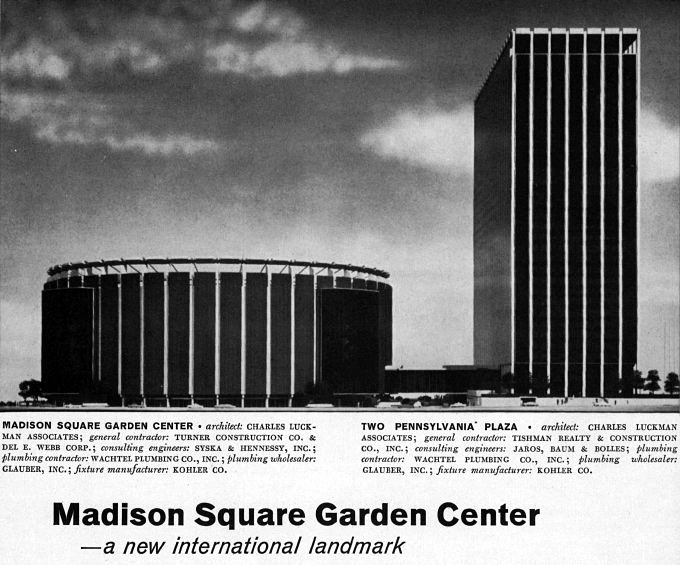

The public outcry was immense: the New York Times called it a “…monumental act of vandalism…” and “…the shame of New York.” Architectural historian Vincent Scully lamented, “Through (Penn Station) one entered the city like a god. Now one scuttles in like a rat.” And Ada Louise Huxtable, the Times’ architecture critic, warned, “We will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.” The glory of “Old” Pennsylvania Station was replaced by the steel and glass of the new Madison Square Garden complex, with the rail station consigned to the “basement” of the Garden.

The result of this outcry was the creation of the New York City Landmarks Commission, the first of its kind in any city in the U.S. Multiple buildings and districts in New York have been preserved since, particularly Grand Central Terminal, New York’s last surviving grand gateway.

The Preserved Train Indicator

The Pennsylvania Station Hutchinson Train Indicator displayed at the Whippany Railway Museum was manufactured by the National Indicator Company of New York, and was one of 44 such Indicators placed at Penn Station’s boarding gates. This now-rare Indicator is unique in that it is the only one intentionally earmarked (albeit partially intact) for preservation purposes when Penn Station was demolished in the early-1960’s.

Oddly enough, at the “new” Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, in a walled-off baggage area near Track 1, there remains yet one other Train Indicator, although it has been compromised since it’s original installation in 1910. It has only one “face”, (originally there were four sides)…but remarkably, it survives to this day in its original location.

The eight-foot section at Whippany was saved in the midst of Penn Station’s demolition in 1966 by the Morris County Central Railroad (a steam-powered excursion line operating out of Whippany, NJ in the 1960’s). The artifact, with it’s ornate, Romanesque crown, was subsequently placed in storage at Whippany. At the same time, the MCC also acquired and preserved the lower portion of another Indicator. Thirty years later in 1996, during the Sesquicentennial year of the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Whippany Railway Museum finally erected the upper section of the Penn Station Indicator. (The surviving lower section was eventually given to a South Jersey collector of PRR items, who continues a long-term process to replicate a full-size Indicator) Today this genuine 1910 PRR artifact stands as a monument to this great citadel of transportation’s past and gives Museum visitors but a glimpse of the grandeur and glory that was ‘Old’ Pennsylvania Station.